Multimedia GIS: A New Tool For Landuse Planning

Markus Weidenbach

Chair for Landuse Planning and Nature Conservation

Ludwig-Maximilians University, Munich

Am Hochanger 13

D-85354 Freising

weidenba@forst.uni-muenchen.de

Go to FORAM Design Project

-

Ulrike Pröbstl

Arbeitsgruppe für Landnutzungsplanung,

Landschaftsökologie und Landschaftsgestaltung

St. Andrä-Str. 8

D-82398 Etting - Polling

Ulrike.Proebstl@t-online.de

Abstract

This article describes the potential for using Geographic Information Systems

(GIS) coupled with multimedia technologies to improve the landuse planning

process. The authors demonstrate, using an actual Landscape Master Plan

for a rural community in Upper Bavaria (Germany) how multimedia and GIS

technologies can be used to improve the communication between a landscape

architect and the local people. The technical details on the "multimedia-enhanced”

GIS and the procedures used to collect and incorporate the digital data

are described. Several computer screen captures from the ArcView

GIS presentation software illustrate the information that can be displayed

using a multimedia GIS.

This article also discusses how the Internet could be used to further

improve communication between all parties involved in a landuse planning

process.

Finally, preliminary results are presented from a study which explored

the acceptability of using multimedia, GIS and Internet technologies in

landuse planning. That study involved both landscape architects and local

citizens.

Additional graphics which supplement this article are available on

the Internet.

Key words:

landuse planning, multimedia GIS, citizen participation, Internet technology

Introduction

The Landscape Master Plan (LMP) is a central element of landuse planning

in Germany (Kiemstedt 1994). It is one component of what is known as the

"Land Use Plan” for a community, and it serves a variety of purposes:

-

It is a repository for information on the region and its community. It

includes, for example, information on soil conditions, on the quality of

water resources, and on all officially registered biotopes. The LMP contains

both current and historical maps which show how the region has evolved

over time.

-

It gives a brief overview of the current form of landuse in the region

and discusses trends in development.

-

It helps landscape architects identify potential landuse conflicts through

analysis of: (a) the information contained in the LMP and (b) the interests

of the local people. Examples of possible conflicts include: planned afforestations

in swampy areas which would destroy valuable biotopes, or new urban development

in sensitive parts of the ecosystem.

-

It provides a framework for the landscape architect who, working in consultation

with the various stakeholders, must provide workable solutions to landuse

conflicts, as well as prepare guidelines for future development in the

region (over about a 15 year timeframe).

Once accepted by the local authorities, the new LMP (which incorporates

the landscape architect's proposals and guidelines) is then integrated

into the Land Use Plan for the community. The landscape architect's proposals

could include: new protected areas, new housing areas, zones for recultivation

and tree planting to improve the landscape aesthetics. The Land Use Plan

is a mandatory planning instrument for the local authorities.

However, the contents of this 20 year old planning instrument, as well

as the planning process itself, are in a constant state of evolution. The

planning conditions and circumstances have changed significantly over the

years. In response to these changes, the LMP has evolved from a "service-plan"

completely designed by a landscape architect, to an instrument in which

public participation plays an important role. It has become a focal point

for discussions on landuse policy, on ecological issues, and on planning

guidelines and objectives.

The Bavarian Ministry for Landscape

Development and Environment now regards a democratic and "citizen friendly"

process as the central element in improving landuse planning in Bavaria

(Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Landesentwicklung und Umweltfragen

1996). Whether or not pre-defined planning goals are achieved is very much

dependent on the way in which the issues of landscape aesthetics and ecology

(which often compete with other public and private demands) are presented

to the town council and citizens.

But not only has the planning process changed. New demands on landuse

planning have arisen. Landscape architects can no longer restrict their

focus to issues of ecological integrity and landscape aesthetics. The resolution

of landuse conflicts and the establishment of long term objectives are

now essential tasks in the landuse planning process. Also, there is an

increasing amount of data which must be integrated into the planning process.

For example, today we have access to more ecological information - information

such as the distribution and quality of biotopes, the presence of endangered

species, the quality of water and the soil conditions. Innovative landuse

planning should therefore meet new standards in at least two areas:

-

the handling and analysis of an increasingly large and complex body of

data, and

-

the presentation and clear communication of that data to stakeholders.

With respect to a democratic and citizen-friendly landuse planning process

(Luz 1995), the use of GIS in conjunction with multimedia and Internet

technologies offers great potential for improving the clarity of data presentation

and in communicating landuse decisions to the community (Cámara

1997, Raper 1997a, Schmidt-Belz et. al. 1997, Shiffer 1995). Digital technologies

can help planners, citizens and officials to communicate in a much better

way. Where people have been restricted to using analogue, paper-based maps,

they can now benefit from the power of GIS and multimedia, requiring only

a laptop computer, projector and screen. This is very important for the

planning process, because guidelines and proposals for ecologically-sound

development will be integrated into the community's Land Use Plan only

if the community council accepts them. Consequently, an important part

of our research was to identify the methodologies and underlying computer

technologies which would be not only necessary, but also available to all

landscape architects in Germany, whether they work in a large urban centre

or a small village in Bavaria. In addition to feasibility, two areas were

of especial interest to us:

-

the reaction of landscape planners to the proposed approach, and

-

the usefulness of this approach to a local community and its citizens.

This study was undertaken as part of the EU funded project, Detailed Visual

and Amenity Design Guidelines for Forestry: Optimising Rural Resource Potential

(FORAM), at the Chair for Landuse Planning and Nature Conservation of the

Ludwig-Maximilians University Munich (Weidenbach & Wild 1997). This

initial investigation into the use of multimedia GIS uses an actual Bavarian

LMP as its basis.

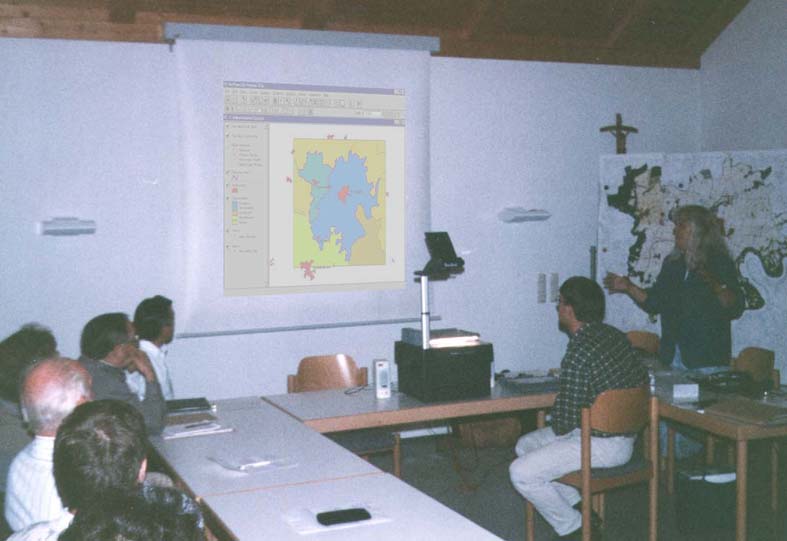

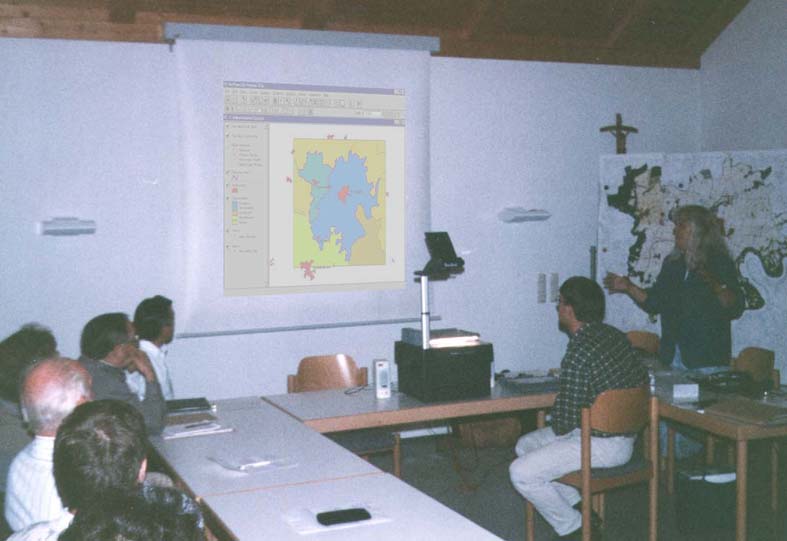

Fig. 1. GIS-based presentation of the Landscape Master Plan to the community

council of the small Bavarian village, Burggen, using a laptop computer

and overhead projector.

Fig. 1. GIS-based presentation of the Landscape Master Plan to the community

council of the small Bavarian village, Burggen, using a laptop computer

and overhead projector.

The Role of GIS in the Planning Process

Nowadays, landscape architects commonly use computers to write reports,

maintain databases and perform spreadsheet calculations. The extension

of digital technologies to activities in landuse planning (e.g., to cartographic

inventories, assessment, planning, and to the presentation of geo-referenced

spatial data ) is the next logical step.

The classic tasks of GIS are the analysis and alphanumeric/graphic

presentation of spatial data (Bill & Fritsch 1994, Haines-Young et

al.1993, Burrough 1986). However, the functionality of a conventional GIS

can be significantly enhanced by the addition of several new data types.

According to Bill 1996, we can differentiate 3 groups of data based on

data source and format:

-

alphanumeric data;

-

vector and raster GIS data; and

-

sound; image and video data.

Like the classic GIS, the enhanced "multimedia GIS” is focused on using

vector and raster data. That data core is supplemented by alphanumeric,

sound, image and video data.

Data Input

At the beginning of the planning process, the availability of digital data

must be determined. The release of spatial digital data is still rare in

Bavaria. Additionally, the price, distribution and licensing policy is

often left unclear. Probably the best spatial data for Bavaria can be found

at the State Survey Branch in Munich, which offers different thematic layers

of the official topographic map in the common DXF format (Drawing Exchange

Format). With the exception of this general data, almost all other landuse

and ecology-related data must be digitised by the landscape planners themselves

- a process which is still very time-consuming and expensive.

Spatial data can be digitised in various ways: Alphanumeric data can

be recorded using text processing or database software. Vector and raster

GIS data can be digitised from orthophotos, maps or sketches and - according

to Warner 1993 - even from distorted terrestrial photos (an elevation model

is needed for this process). New methodologies have been researched by

Kias 1996 to digitise site data directly in the field using portable pen

computers and geo-referenced background information such as digital maps

or orthophotos. Sound, photos and videos can be recorded in the field by

means of digital or analogue devices such as standard video recorders and

35mm cameras.

The spatial accuracy of digitised polygons, points and lines is one

of the most important issues in GIS. Accuracy here depends primarily on

the quality of the available, basic information. The greatest accuracy

can be achieved by digitising all sites from aerial stereo photos - something

which is not always practical since the planner must integrate a variety

of data sources and formats into the GIS. For instance, in addition to

the photogrammetric landuse interpretation based on orthophotos or aerial

stereo photo models, the mapping of landscape features from existing paper

maps still remains necessary. Those maps are often not up-to-date. Further,

their scale may differ from the scale of the LMP, and this can introduce

additional inaccuracies.

Interactive Data Analysis on Demand

The ability of GIS to analyse ecological and landscape-related spatial

data has often been discussed and demonstrated (Reis Machado & Ahern

1997, Bayerische Akademie für Naturschutz und Landschaftspflege 1996,

Haines-Young et al. 1993). In our research, we were primarily interested

in the ability of GIS to do interactive analysis - that is, analysis

on demand. For instance, during a presentation to a local community, a

member of the audience may wish to know if any officially registered biotope

is located on his/her property, its ecological features and/or its exact

size.

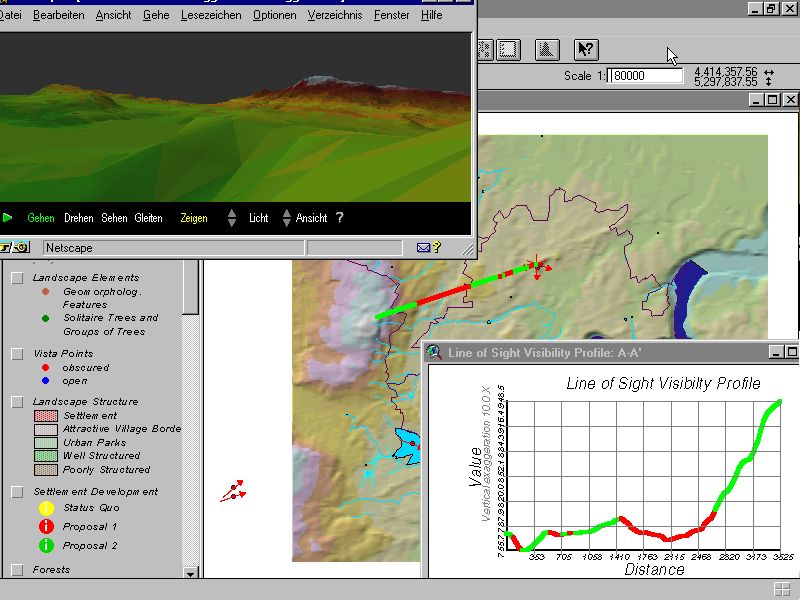

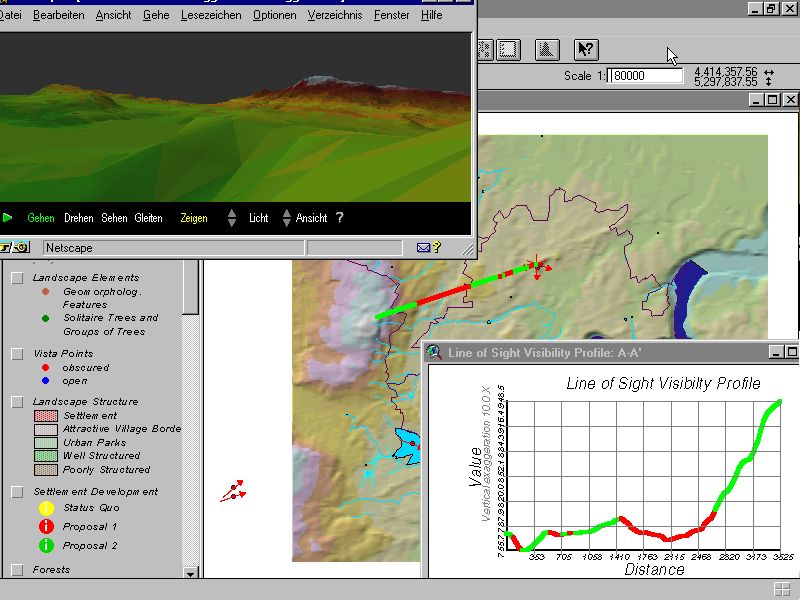

Another advantage of using digital data and GIS is the ability to analyse

3-dimensional landscape models which form the basis for visibility, slope,

aspect, line-of-sight or watershed calculations. Queries of this nature

can also be handled, providing the necessary base data is available (see

Fig. 4).

Multimedia elements can play an important role in visual analysis. For

example, a photo taken from a registered viewpoint which appears on the

screen when that viewpoint is clicked, completes the visibility analysis.

Also, a demonstration of how scenery will change over time can be done

by using the multimedia GIS to display photorealistic simulations of successive

stages of development (see Fig. 3), or by linking video clips or photo

sets (for example, a sequence of images taken over the past several decades).

Using the data from the LMP we chose for this study, we used this capability

to answer a question on how an afforestation might influence the scenery.

We generated a photo animation which ran as a

video and showed how the landscape changed as the young stand evolved to

become a mature forest (www.lnn.forst.uni-muenchen.de/daten/foram/mmgis/ani101.gif).

The use of digital technologies enables the landscape architect to

present information to audiences in a flexible and transparent way, even

though the amount and complexity of the underlying data continues to increase.

One example here is the ability of GIS to overlay selected thematic maps,

allowing the viewer to see complex relationships at a glance. Using this

technique, landuse conflicts can be quickly identified, and displayed with

a level of clarity and legibility that cannot be achieved by analogue cartographic

illustrations. Additionally, turning different map layers on or off can

be useful in illustrating the various steps in the planning process.

Visualisation and Data Presentation

As mentioned above, a Landscape Master Plan that is easily understood is

essential for the acceptance of design proposals. A client-friendly analysis

and presentation of planning results has become an important factor in

successful landuse planning. A GIS which is able to simulate geo-referenced

landscape stimuli is a suitable tool for creating a general awareness of

the relevant planning issues. The multimedia computer presentation possible

with such a system facilitates the illustration of often very complex planning

goals and creates a sensitivity for landuse related conflicts. Sustainable

implementation of a landuse plan can only be achieved if citizens are fully

aware of all the issues and can make informed decisions.

We selected the GIS software ArcView 3.0 with the Spatial Analyst

extension and Netscape Gold 3.0 to present the data in the LMP of

a rural community in Upper Bavaria. ArcView runs on Windows95 and encompasses

all the multimedia functionality of the platform. We used a laptop computer

with two external speakers for our presentation. To project the data on

the screen we placed the removable LCD display of the laptop onto a standard

overhead projector.

The following paragraphs describe the digital data components of the

LMP. The various thematic and planning maps were presented as separate

"views" using the ArcView software. The vector data were ArcInfo coverages,

ArcView shape files and vectors in Drawing Exchange Format (DXF). The following

data types were added to the vector data in ArcView:

-

tables in dBase format - necessary for the display of site-specific

data via a mouse click on the site;

-

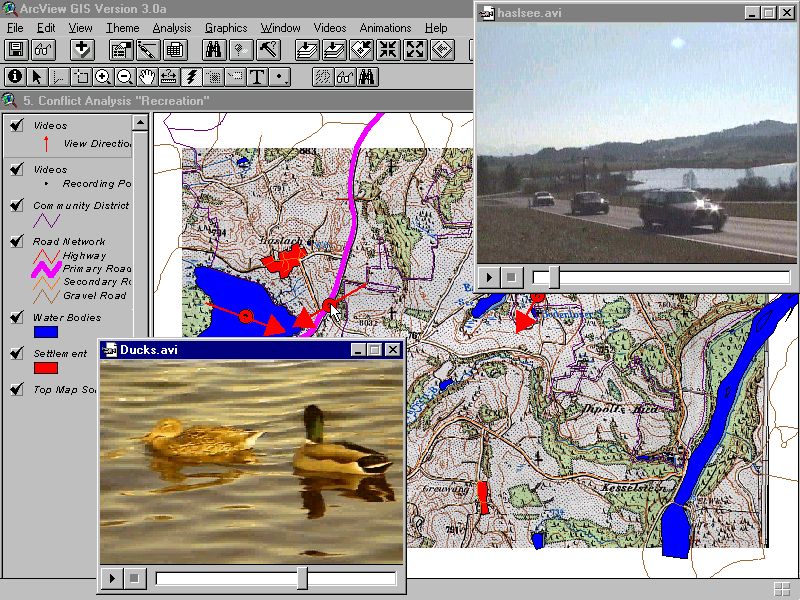

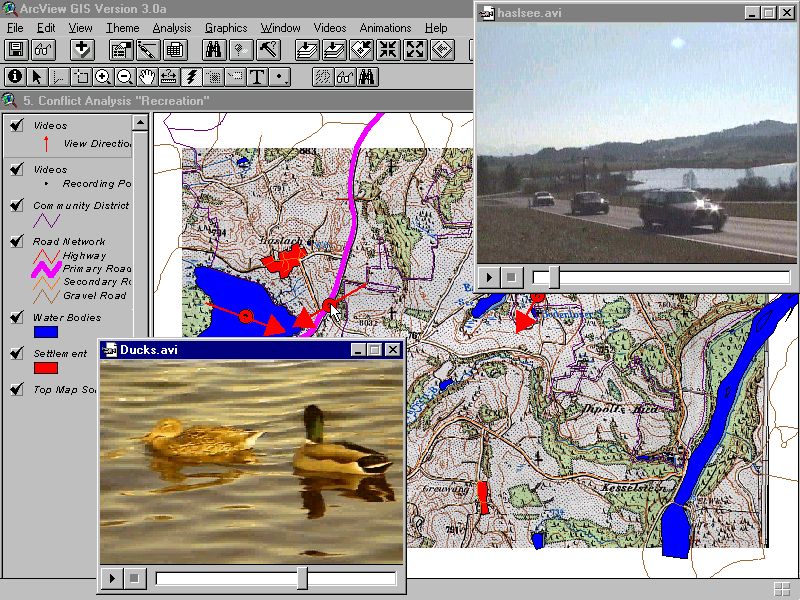

videos in Video for Windows format - used to provide a visual and

acoustic landscape impression (the videos were related to the mapped recording

point);

Fig. 2. Videos with sound illustrate the conflicts with respect

to recreation

-

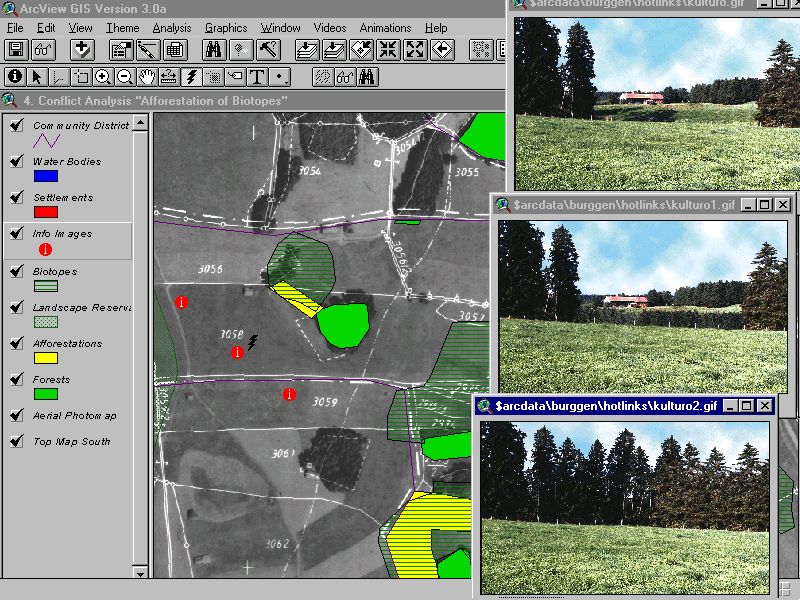

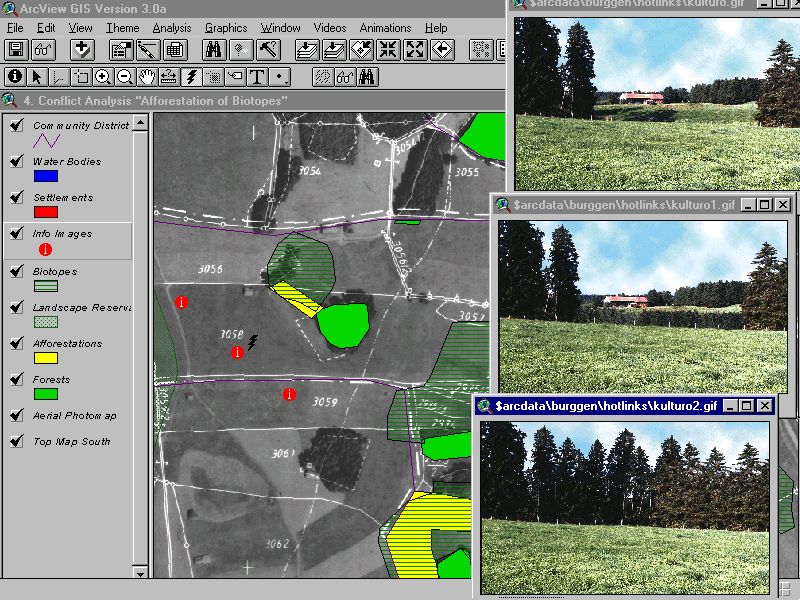

images in JPEG, GIF and TIFF format - used as background information (b/w

topographical maps and orthophotos) and illustrate areas of interest in

a photorealistic way (terrestrial, site-related colour photos);

-

image animation in GIF format - used to illustrate changes in the landscape

over time;

Fig. 3. Photoshop simulation of growth of afforestations

helps to illustrate future conflicts

-

an ArcInfo Shaded Grid - gives a 3-dimensional landscape impression;

-

an ArcInfo TIN (Triangulated Irregular Network) in VRML format (Virtual

Reality Modelling Language) - describes space conditions in 3 dimensions

and allows a realistic, interactive flight through the landscape even in

the WWW. You can run the VRML model from the Internet using, for example,

Netscape Gold 3.0 (www.lnn.forst.uni-muenchen.de/daten/foram/mmgis/Burggen0.wrl).

Fig. 4. Three-dimensional landscape analysis with line of sight

calculations (lower right) and a Virtual Reality Landscape Model (upper

left).

Data Dissemination and Exchange via the Internet

In this section we outline our vision for the future evolution of landuse

planning. Some of what we describe is already a reality. Other elements

(such as an interactive LMP on the Internet) are likely to become a reality

very soon, given the speed with which Internet technologies are evolving.

Data storage is a central issue in the maintenance and exchange of digital

material. Commonly used storage media and data formats will simplify data

handling in the longer term. System-independent data formats, such as most

of those used on the Internet, will likely have a longer "life expectancy"

than other formats. Although there is already a "next generation" CD on

the market (DVD-ROM, Digital Versatile Disk), the ISO standard CD ROM is

still a good choice for the storage of data, since it is in widespread

use. The data encoded on a CD ROM is write-protected and can be read by

most of the newer PC, Macintosh and UNIX workstations.

A key advantage of using digital data is the ability to rapidly exchange

information over networks such as the Internet, as well as over Intranets

and Extranets (Raper 1997b, Strasser & Wasserburger 1997). The increasing

network links between government authorities, landscape architects, communities

and private Internet users, opens new avenues for public participation

and communication between all stakeholders in a landuse planning process

(Werner & Bayerische Staatsregierung 1997). The discussion focuses

on three such groups:

-

the authorities concerned with landscape design and nature conservation;

-

the citizens who live in the study area; and

-

the local communities and their representatives

The landscape architect frequently co-ordinates planning steps with the

responsible authorities, and obtains the basic information required. In

future, the use of digital data could facilitate the information flow between

authorities and the planner via the Internet. Questions and disagreements

over proposed measures could be handled verbally or graphically by e-mail,

using the latest GIS online maps. The final LMP could be submitted to the

responsible authorities digitally over the Internet, thus saving the costs

of copying and mailing paper-based maps and other documents.

Normally, all citizens of a community in the study area are informed

about the planning stages and procedures at public meetings of the community

council. In the federal state of Bavaria, the LMP must be approved by the

community council. There is a legal time limit for citizens to file any

objections. If the proposed LMP were published on the Internet, access

by interested parties would no longer be restricted to office-hours, public

gatherings and official meetings late in the evening, as is now the case.

Thus, Internet publication of the LMP, along with the time limit for public

response, makes good sense. Even filing an objection by e-mail would be

possible, although there are legal issues which would have to be addressed.

Answers to the technical issues of Internet publication can be found

on the Internet itself. The file formats currently in use on the World

Wide Web (WWW) have now become reasonably standard, and can be read by

a wide variety of computers and operating systems. Most Web Browsers are

now able to process JPEG and GIF images, and replay sound (*.wav) or video

(*.mpg, *.avi) files. The recent extension of Browser capabilities (through

Plug-Ins, Java Applets and Scripts or Active-X), enables users to navigate

3-dimensional landscape models most commonly in the VRML-format in real

time, to play sound and music, to make phone calls via the Internet, or

to send e-mail messages directly through the Browser.

The ”helper” programmes and Java scripts required to display and interact

with digital maps on the Web can be downloaded from the Internet. This

includes, for example, the user shells from Autodesk (www.mapguide.com)

and Esri (www.esri.com/base/products/internetmaps/ internetmaps.html) which

can be used to receive and read vector and image (*.GIF) data. The zoom

command of these shells enables the receiver to ask for more detailed data

from the server, which then delivers the information appropriate for the

chosen scale. Additionally polygons and points on the online map can be

linked to reports or tables.

General Acceptance of New Digital Media

Landuse planners have taken their first steps into the digital world. Their

acceptance and expectations of new technologies are important factors in

stimulating the adoption of those technologies. However, using the latest

computer techniques does not necessarily guarantee their acceptance - neither

by professional planners nor by citizens, the "end consumers" of the planners'

work. Many people are still not familiar with computers and, therefore,

might react negatively to the adoption of GIS and digital technologies.

The extent to which these technologies can be successfully implemented

- at least in the near term - is still an open question.

The successful implementation of a multimedia GIS in landuse planning

work depends on its acceptance by two groups:

-

professional landscape architects and planning authorities, the ”active”

users of the technology; and

-

local citizens, the "passive” users and "end consumers” of the planning

data.

We therefore carried out a study to gather feedback from the two groups,

and learn the extent to which they felt the new technologies might improve

the public planning process (Weidenbach, in preparation). Preliminary results

from that study are presented below.

Material and Methodology

In our study, we used a multimedia GIS to give presentations to five groups

of people. The data we used was from two sources: (1) the previously-mentioned

LMP for the village of Burggen, and (2) a comparable GIS project in the

Upper Danube Valley Nature Park. After the presentations, each group openly

discussed their feelings and general impressions. A questionnaire was then

distributed to collect data for a subsequent statistical analysis. The

results of the survey will be published when that analysis is completed

in mid-1998. In this paper we discuss only the methodology we used, and

present results from several of the group discussions.

Guided discussion with an audience (sometimes called ”group exploration”)

is an essential tool for uncovering emotionally-influenced concerns, fears,

preferences and dislikes, and doing so in a very deep and individual way.

Misunderstandings and the reasons underlying a people's responses can usually

be brought to light. Our methodology was based on similar work done in

May 1997 by Prof. M. Keppler, who researched preferences of forest visitors

as part of the above-mentioned EU FORAM project (Keppler Konsumforschung

GmbH 1997, Weidenbach & Wild 1997). Prior to each of our presentations,

the test group was told that there would be a group discussion following

the presentation, and was therefore asked to follow the presentation very

carefully. These discussions were guided by the authors using a prepared

framework of questions and topics. Some examples follow.

-

How did you feel about our presentation of environmental data using computer

and GIS technologies?

-

Was the presentation attractive? Did you like it?

-

What are the advantages and disadvantages of this type of presentation?

-

Do you see any possibilities for the manipulation of information?

-

Environmental/spatial data may soon be available to everyone on the Internet.

Would you take advantage of this and download landscape-related data?

-

Do you see any problems in this method of data exchange?

Each group discussion took about 30 minutes. Sessions were tape recorded

and written notes were taken.

One important criterion for the selection of study groups was familiarity

with the regions being presented. Three of the five groups had this familiarity.

This was helpful for obtaining critical feedback on the realism and clarity

of the presentation.

The following table summarises our test groups and presentations:

| Date |

Location |

Audience |

n |

Content of Presentation |

| 04.06.97 |

Nature Park Centre Upper Danube Valley in

Beuron |

Participants of symposium: Nature Conservation

and Tourism |

14 |

ArcView project of Nature Park Upper Danube

Valley |

| 11.06.97 |

Community Centre nearby Bruchsal |

Participants of symposium: GIS in landscape

planning |

44 |

ArcView project of Nature Park Upper Danube

Valley |

| 24.06.97 |

Community Centre Burggen in Bavaria |

Public meeting of the community council |

14 |

Landscape Master Plan of the community of

Burggen |

| 04.07.97 |

University of Salzburg |

Participants of GIS symposium: AGIT97 |

32 |

Landscape Master Plan of the community of

Burggen |

| 26.07.97 |

Nature Park Centre Upper Danube Valley in

Beuron |

Participants of student excursion: Upper

Danube Valley |

30 |

ArcView project of Nature Park Upper Danube

Valley |

Table 1. Date, location, audience and content of presentation

For purposes of this article, we will focus on the responses of the

professional planners (from the three symposium groups), and of the citizens

from the village of Burggen. The groups differed mainly by age and profession.

People in the symposium groups were mainly in the 30-50 age group and were

mainly employed or self-employed landscape architects, and government planners.

Most of the people in the Beuron group had no GIS background. GIS experience

was more common in the Bruchsal and Salzburg groups. The citizens of Burggen

were mainly self-employed people and farmers. They were somewhat older

than people in the symposium groups, with a higher percentage of people

in the 45-65 age group. About two thirds of the participants in all groups

were men.

Results of the Group Explorations

The following paragraphs briefly summarise the feedback we received from

four of the five study groups, namely, the citizens from the village Burggen

and the professional planners in the three symposium groups.

In general, feedback on the multimedia GIS presentation was positive.

No one rejected the presentation outright, although there were a number

of critical comments.

Viewing the computer screen projection with its various maps, images,

videos and tables was, for the most part, not a problem for the audience.

Only two people complained that their eyes became exhausted. The generally

positive feedback here probably indicates that people are becoming used

to electronic images, by working increasingly with computers, or perhaps

even from frequent television watching.

Among both landscape architects and citizens, there was high general

acceptance of the new technologies, albeit for two different reasons:

(1) passive acceptance, arising from a feeling of being forced

to use the new technologies (e.g., to compete with other professionals

involved in landuse planning, or because the introduction of these technologies

was seen as inevitable)

(2) active acceptance, arising from a profound conviction that

a multimedia GIS is a useful and powerful tool for communicating landuse-related

data.

The second opinion was most often expressed by people who already had some

experience with GIS (e.g., the symposium groups in Bruchsal and Salzburg).

On the other hand, people who had no prior experience with GIS (chiefly

the symposium group in Beuron and citizens from the village of Burggen)

felt that computers and GIS were tools for the future, rather than for

the present. For the citizens of Burggen, the presentation was novel and

strange. They liked it chiefly because of the ability to present different

themes in succession, and because of the photorealism of the simulations

(e.g., showing the impact of afforestations and new housing developments).

The ability of certain presentation elements (e.g., geo-referenced photos,

videos, shaded and virtual landscape models) to help people visualise impacts

of changes was a frequently mentioned advantage of the multimedia GIS over

analogue maps. Even though the citizens of the village Burggen felt that

the digital technologies improved the clarity of the presentation, most

of them were reluctant to do away with analogue paper maps on the wall!

In summary, both professional landuse planners and lay citizens alike

identified three significant advantages of the multimedia GIS:

-

the flexibility with which the system can display thematic and planning

maps, notably: its ability to: (a) display different themes in succession,

(b) generate map overlays and (c) zoom in and out to a specified level

of detail;

-

the ability of the system to integrate, link and display different types

of data (e.g., tables, videos and images); and

-

the interactive nature of the system (i.e., its ability to handle ad hoc

queries during the presentation).

The citizens of Burggen criticised the quality of the sound videos. They

also expressed a concern that planners could unscrupulously manipulate

data to suit their own ends (for example, by selectively editing a video

clip). In the critical comments from all study groups, there were three

items which repeatedly surfaced:

-

the digital technologies are novel and strange, and people are not yet

familiar with them;

-

the objectivity and credibility of the data is questionable, due to the

possibility of unscrupulous manipulation and the ”unscientific” nature

of the multimedia elements; and

-

the technical quality of certain elements in the presentation (chiefly

videos and images) was criticised.

The professional landscape architects and government officials were asked

about their expectations with respect to multimedia GIS technologies, and

about catalysts and barriers to their adoption. Self-employed landscape

architects especially expressed concerns about the cost of the new technologies,

and about the time they would need to invest in order to use them effectively

and efficiently. The need to be competitive with other planners was often

mentioned as a driving force and catalyst in the adoption of new technologies.

The most frequently expressed expectations from a multimedia GIS were improving

the planner's ability to:

-

maintain, manage and issue queries against data;

-

design convincing digital presentations;

-

analyse and manipulate data; and

-

produce simulations (e.g., of future landscape changes).

Finally, groups discussed the potential use of the Internet (chiefly the

WWW) to exchange and communicate spatial data, such as an LMP. Predictably,

those who already use the Internet professionally, or who were most likely

to use it in the future (e.g., government officials and some of the landscape

architects) were much more receptive to its potential use in landuse planning

than those with no Internet experience. Current Internet users felt that

it saved them time in their daily planning work, and that its use in exchanging

data with planning authorities could shorten the planning cycle.

Group members with little Internet experience - primarily the citizens

of Burggen and the landuse planners in Beuron - were sceptical about its

usefulness. They argued that the Internet is a future technology, and that

few people in the general population currently use it. They also felt that

it is complicated to use. Experienced Internet users criticised the poor

maintenance and documentation of much of the data available through the

Internet, pointing out that data could easily out-of-date, and that often

it is not clear who is responsible for what is published.

Conclusions

The computer is neither able to replace a field trip with a landscape architect,

nor reproduce the complexity of an individual's landscape perception in

a satisfying way. But we can use computer technology as a tool to raise

the public's awareness of the importance of nature and landscape protection,

as well as to involve people in the planning process itself. If this can

be accomplished, there is a much greater chance that the public will accept

and be willing to support the implementation of landuse planning proposals.

The digital presentation of multimedia-enriched landscape data combines

the realistic illustration of a landscape with the ability to obtain site-specific

data in an ad hoc, interactive manner. This is something which cannot easily

be done using conventional analogue maps and separate slide or video presentations.

Another advantage of digital presentations is their flexible handling of

scale through the 'zoom' feature of the GIS. Using this, one can easily

combine small and large scale maps of the same area. This can be useful

in, for example, helping a viewer better understand the importance of ecological

”microstructures” within the larger ”macrostructures” of a landscape.

Working with a GIS means an additional investment of time and money

for self-employed landscape architects. A detailed record of the time we

spent preparing our digital presentation of the LMP was not kept. Although

our prototype presentation took several months to complete, this can be

expected to decrease considerably when digital presentations become routine

part of landuse planning.

Discussions with the test groups revealed that a digital presentation

- through elements such as sound, images, colour and interactivity - can

influence an audience more than can a conventional analogue presentation.

The use of background music, and the manipulation of images, sounds and

videos must therefore be looked at very critically.

Our study indicates that use of the Internet is not a viable alternative

for people who are unfamiliar with computers. In spite of the present popularity

of the Internet, regular use of the WWW in Germany is not yet widespread

among the general population. One of the reasons may be that there are

currently only a few Internet services (e.g., home banking) from which

the general population can benefit. However, the growing number of recently

installed Community Networks (Bürgernetze) in Bavaria (Werner &

Bayerische Staatsregierung 1997) indicates that interest in using the Internet

and the WWW (for purposes other than entertainment) is increasing. The

group discussions in this project have shown that people with little or

no Internet experience are leery of what appears to be a complicated and

strange technology. New techniques recently presented in Berlin in the

exposition Internationale Funkausstellung (Haas & Tunze 1997), which

integrate Internet and television technologies, have the potential to deliver

Internet services to people in a more "familiar" format. This may be an

important factor in the broadening the acceptance and usage of the Internet

and WWW.

Digital technologies make it easier for landuse planners to manipulate

data to suit their own ends. These technologies will play an important

role in landuse planning only if planners use them with a sense of responsibility.

The expense of preparing a digital LMP is justifiable providing the

digital data is not converted back to India-ink drawings in order to make

future revisions. The data must remain in its digital form for future processing,

dissemination and presentation.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Gordon Runtz in Vancouver and the anonymous revisers from

Forest & Landscape Research for the critical review of the article.

Literature

-

Bayerische Akademie für Naturschutz und Landschaftspflege (ed.) 1996:

GIS in Naturschutz und Landschaftspflege. Laufener Seminarbeiträge

4/96, Laufen, 88 pp.

-

Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Landesentwicklung und Umweltfragen

(ed.) 1996: Leitfaden zur Fortentwicklung des gemeindlichen Landschaftsplanes

als Teil des Flächennutzungsplans in Bayern: "Landschaftsplanung am

Runden Tisch", München, 34 pp.

-

Bill, R. 1996: Grundlagen der Geo-Informationssysteme: Vol. 2: Analysen,

Anwendungen und neue Entwicklungen.,Wichmann, Heidelberg.

-

Bill, R. & Fritsch, D. 1994: Grundlagen der Geo-Informationssysteme:

Vol. 1: Hardware, Software und Daten, 2. Issue, Wichmann, Heidelberg.

-

Burrough, P. A. 1986: Principles of Geographical Information Systems for

Land Resources Assessment. Reprint 1994, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 194pp.

-

Cámara, A. 1997: Interacting with Spatial Data: The Use of Multimedia

and Virtual Reality Tools. Publication for the conference: Geographic Information

Research at the Millenium: GISDATA Final Conference. Le Bischenberg, France,

1997. Web page: www.shef.ac.uk/uni/academic/D-H/gis/camara.html

-

Haas, K. & Tunze, W. 1997: Die neuen Bouquets kommen nicht vom Floristen.-

Der Stern 36/97: 85-88.

-

Haines-Young, R. et al. (eds.) 1993: Landscape ecology and GIS. Taylor

& Francis, London, 288pp.

-

Keppler Konsumforschung GmbH (ed.) 1997: Erlebnisqualität des Waldes:

Ansätze für eine Kategorienbildung zur Ästhetik des Waldes,

unpublished expertise. Chair for Landuse Planning and Nature Conservation,

Freising.

-

Kias, U. 1996: Pen-Computer-Einsatz und GIS in der landschaftsplanerischen

Bestandsaufnahme - dargestellt am Beispiel der Strukturen- und Nutzungskartierung

im Rahmen der Ländlichen Neuordnung in Bayern. Publication for the

4. German ArcInfo User Conference in Freising.

-

Kiemstedt, H. 1994: Landscape Planning: Contents and Procedures. Ministry

for Environment, Nature Protection and Nuclear Safety, Bonn, 34pp

-

Luz, F. 1995: Zur Akzeptanz landschaftsplanerischer Projekte. Determinanten

lokaler Akzeptanz und Umsetzbarkeit landschaftsplanerischer Projekte zur

Extensivierung, Biotopvernetzung und sonstiger Maßnahmen des Natur-

und Umweltschutzes, Verlag P. Lang, Frankfurt, Bern.

-

Raper, J. 1997a: Progress Towards Spatial Multimedia. - In: Craglia, M

& Couclelis, H (eds.): Geographic Information Research., Taylor and

Francis, London

-

Raper, J. 1997b: Geographic Information on the Web. Publication for the

conference: Geographic Information Research at the Millenium: GISDATA Final

Conference. Le Bischenberg, France, 1997. Web page: www.shef.ac.uk/uni/academic/D-H/gis/raper.html

-

Reis Machado & Ahern 1997 (eds.): Environmental Challenges in an Expanding

Urban World and the Role of Emerging Information Technologies. National

Centre for Geographical Information, Lisbon, Portugal, 521pp.

-

Schmidt-Belz, B. et. al. 1997: Validierung einer WWW-basierten Unterstützung

für die Stadt- und Raumplanung. - In: Dollinger, F. & Strobl,

J. (eds.): Salzburger Geographische Materialien Vol. 26: 391-396.

-

Shiffer, M. 1995: Interactive multimedia palling support: Moving from standalone

systems to the WWW. - In: Interactive GIS and Multimedia in Environmental

Planning: Planning and Design. Vol. 22

-

Strasser, D. & Wasserburger, W. 1997: Interaktive Publikationen von

GIS-Daten über das Internet. - In: Dollinger, F & Strobl, H. (eds.):

Salzburger Geographische Materialien Vol. 26: 417-420.

-

Warner, S.W. 1993: Considerations when measuring from a single photograph:

positional uncertainty of digital monoplotting. In. Norsk Geogr. Tidsskr.

Vol. 47: 39-50.

-

Weidenbach, M. (in preparation): Möglichkeiten und Grenzen Geographischer

Informationssysteme und neuer digitaler Medien in der Forst- und Landschaftsplanung.

Dissertation am Lehrstuhl für Landnutzungsplanung und Naturschutz,

Ludwig-Maximilians Universität, München.

-

Weidenbach, M. & Wild, P. 1997: Detailed Visual and Amenity Design

Guidelines for Forestry: Optimising Rural Resource Potential, Consolidated

Annual Progress Reports, Chair for Landuse Planning and Nature Conservation,

University Munich, not published, web page: www.lnn.forst.uni-muenchen.de/daten/foram.

-

Werner, A & Bayerische Staatsregierung (eds.) 1997: Den Bürgern

einen tatsächlichen Nutzen bringen: Ein Gespräch mit Staatsminister

Bocklet - BayernOnline. 2/97:1-5

List of Tables and Figures

Table 1. Date, location, audience and content of presentation

Fig. 1. GIS-based presentation of the Landscape Master Plan

to the community council of the small Bavarian village, Burggen, using

a laptop computer and overhead projector.

Fig. 2. Videos with sound illustrate the conflicts with respect

to recreation

Fig. 3. Photoshop simulation of growth of afforestations

helps to illustrate future conflicts

Fig. 4. Three-dimensional landscape analysis with line of sight

calculations (lower right) and a Virtual Reality Landscape Model (upper

left).

Go to FORAM

Fig. 1. GIS-based presentation of the Landscape Master Plan to the community

council of the small Bavarian village, Burggen, using a laptop computer

and overhead projector.

Fig. 1. GIS-based presentation of the Landscape Master Plan to the community

council of the small Bavarian village, Burggen, using a laptop computer

and overhead projector.